Tidying Up with Landscape Architects

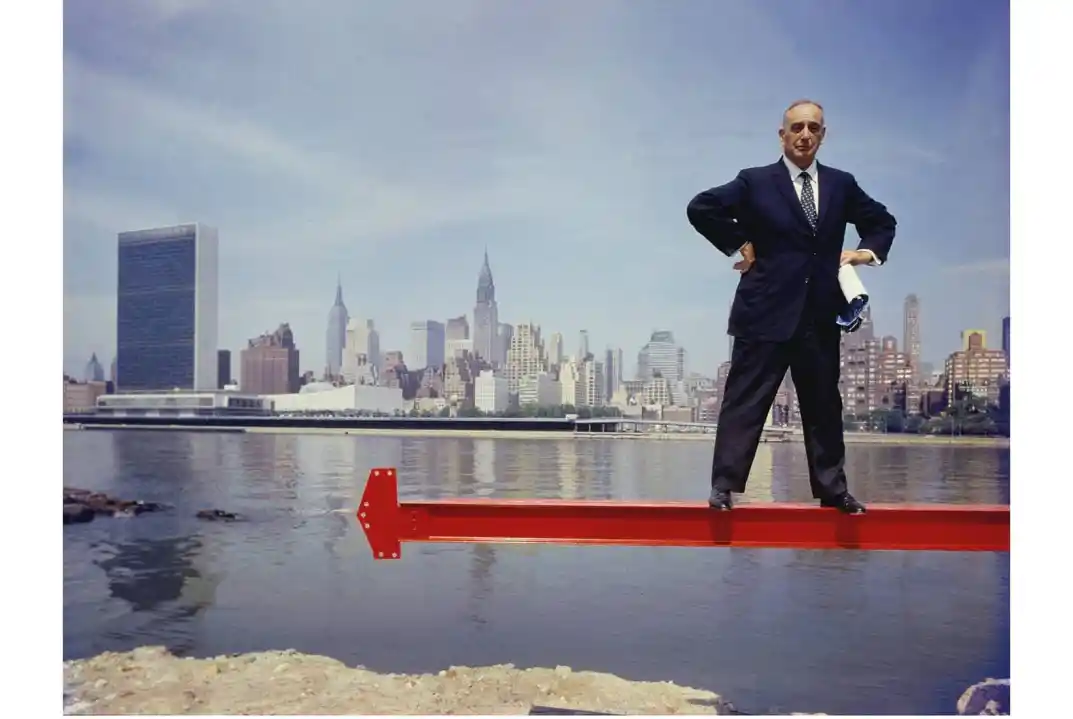

In the mid-1930s in the United States, proponents of the Good Governance & Reform movements who had initially supported Robert Moses’ rise to influence were concerned. Moses had leveraged unprecedented New Deal programs to accumulate enormous experience and power and was growing increasingly blasé in the exercise of this power to reshape New York.

In the case of one bridge project chronicled in Robert Caro’s incredible book The Power Broker, reformers were worried that Moses would

‘destroy the delicate natural balance of a marshland to make a concrete lined lagoon’ a delicate natural balance that, reformers feared ‘it did not lie with the power of man to restore.’

Today, at the end of the beginning of the 21st century, its through this dynamic in reverse that landscape architects most often look to position ourselves. Robert Moses and the attitude he’s become totemic of undoubtedly did and do ‘destroy the delicate natural balance’, but today landscape architects make the case that ‘the power to restore’ does in fact lie within humanity’s grasp and that we are the profession best placed to exercise it.

There are problems that arise from this well-meaning posture, and they’re problems that have become more evident to me after time in commercial practice than they were when I was tucked safely away on Level 7 of the RMIT Design Hub finishing my masters. Namely, in positioning and spruiking ourselves in terms of restoration, what we inevitably come to represent, in the eyes of your typical architect or engineer, is the redemption of their otherwise difficult to justify excesses. I find well meaning people (and most architects are) broadly anxious about what we Doers are Doing in the world. They know (like me) that the impulses to Build Beautiful Things and to Get Things Done are essentially Good and optimistic ones, but as well-informed people they also know that demolishing buildings that are basically fine, pouring thousands of tonnes of concrete, and the inescapably compromised nature of extractive supply chains essential to Building many Beautiful Things are becoming increasingly difficult to justify.

Most people I know in the built environment professions are (like me) foundationally uneasy about how they can justify the environments they build.

And often in the dynamics of live projects I find it’s the absolving of these underlying anxieties that becomes the landscape architect’s most valuable contribution to the design team. Whether it’s through the restoration of indigenous vegetation, environmental remediation, or increased canopy cover: the really compelling restoration we often find ourselves offering - the one that pays the bills - is the restoration of the self-confidence of well-meaning architects who are regrettably finding it increasingly difficult to justify their impulse to Build Beautiful Things while also still being able to look their kids in the eye.

In her very good essay Sustaining Beauty. The performance of appearance, Beth Meyer observes the familiar misogynistic dynamic whereby the other built environments professions err toward being

dismissive of landscape design and constructed nature as feminine, informal, soft, unstructured, anti-progressive and nostalgic.

This observation rings true to me, its one I think would feel familiar to any LA who spends any amount of time in design team meetings. I’d actually take it further and say that the typical relationship between an architect and landscape architect tends to model itself intuitively and insidiously on the old, conservative, traditional gender binaries of doer & redeemer, actor & mender, builder & justifier.

Where I depart from Meyer is in acknowledging a share of agency. It is not just that we are subjected to this binary, we have also made a profession of playing into its dynamics. We have made careers and livings participating in this relatively productive back and forth. I note this not to defend it but to name it, because as any serious person knows, the real test of character comes not when we are afforded agency but when we take responsibility for it.