Have Playgrounds Gone to the Dogs?

Chris Alexander was a stirrer; he was stirring when he wrote

‘no self-respecting child would play in a playground’

One thing I learn from Chris’ mistakes is that if you’re serious about an issue you don’t stir, because if you’re serious about an issue you know that stirring (while very satisfying in the first instance) diminishes the effectiveness of your message.

Discipline and the long view.

His point, while self-sabotaged, is clear. Children, for us, inhabit a reified space of innocence, wonder, and undimmed creative potential. We see them in themselves, and for us, as wellsprings of inspiration and awe.

And so a child who is happy and contented playing in a pre-figured scheme conceived by the agents of mass-manufacturing (playground suppliers) somehow fails to live up to a child’s prescribed role.

When the playgrounds we build in the world are mass-manufactured then so are the stories embedded in those spaces. Nearly every playground supplier offers some version of the pirate ship playground. You can have a pirate ship by the sea, a pirate ship in Broken Hill, it doesn’t matter; the story that children are invited to enter and play through is pre-conceived, pre-packaged, and a child’s interaction with it is pre-empted by the industrialists. It’s the package deal.

The issue for me here is not as much repetition as it is unexamined repetition. Repetition and replicability are great. In a world where the fight to afford everyone the building blocks of a good life doesn’t end, the productivity and affordability benefits of industrial processes and repeatable elements are gains only a deeply unserious person would sneer at.

But it’s the unexamined repetition that I can’t quite get on board with.

The Cattle Truck Playground is an example of this. It takes the bones of the Pirate Ship Playground, a simple story-scenario spatialised through replicable parts, and applies that logic to a Cattle Truck, inviting children in to play at taking on the role of cows in the truck.

And so we see that sometimes the unexamined meme doesn’t land. Here the industrialists have tried to adapt their library of products to a unique, site-specific story. But in the outcome we see that they are no story tellers, they are not skilled at adapting their generic material to the idiosyncrasies of a place.

The cattle truck playground is alarming; its transgressions feel like those of a horror movie. I don’t doubt that the kids (pre-disposed to transgression) love it, but we are left with a feeling that the industrialists do not know what they are doing here. I see in this project the thrill of transgression for the industrialists and for the kids, but I think in the longer term we’ll wish we had had landscape architects working on this project. Encouraging children in our care to play as the living meat of industrial farming is not, I don’t think, a healthy kind of transgression to invite children into.

Levi Strauss famously said that

‘Animals are good to think with’

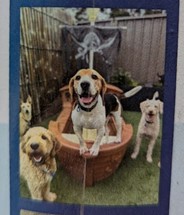

And I think that the Pirate Ship Dog Playground definitely illuminates something about the stories we tell with playgrounds.

What is so obvious about the Pirate Ship Dog Playground that it almost feels silly to point out is that the pirate ship is not for the dogs. The dogs, they don’t get anything from being on the pirate ship. I’m no expert in dog brains but I feel pretty confident in suggesting that they have absolutely no understanding of the cultural place playing at piracy holds in the early 21st century.

If we were designing for what the dogs wanted to play with what we’d likely see in this image might be a washing line full of owners clothes or some kind of a swamp filled with mixture of mud and the poo of various animals.

But that’s not what we see.

And so the illuminating questions that’s good to think with becomes:

If not for the dogs, then who is this pirate ship for?

The answer, again, is almost painfully clear. The pirate ship is for the owners of these dogs, who are paying upward of $60 a day to keep them at dog daycare, and who expect a certain degree of entertainment value in exchange as part of that service. So, it’s not actually even just that the Pirate Ship is for the owners, it’s that the experience of the dog playing on the Pirate Ship is for the owners, is a service provided by this company to the owners.

And so of course this prompts questions. We presume that we design playgrounds for kids, what the Pirate Ship Dog Playground shows us however is that it’s very easy to feel like we’re doing something for a particular user when in fact the actual wants and needs being addressed are those of someone else entirely.

Do we always design playgrounds for kids?

Or is it possible that we sometimes unwittingly slip into a mode of designing for what we, or what parents, want or expect to see kids doing in a playground?

Again, it’s the unexamined reproduction that’s the issue here. It’s no coincidence that the Pirate Ship Dog Playground is a meme of a go-to off-shelf kids’ playground. I think what we always need to do, as landscape architects concerned always with the specifics of a place and the specifics of its actual users, is to carefully parse the replicable elements we bring into a project. They’re valuable, they’re essential to the design process, but they always carry baggage with them. If we do this, if we bring together what we have and what we find with clear-eyed care and knowledge, playgrounds might some day go to the dogs.